THE ARMED FORCES

War doesn’t happen the way it used to last century. It has evolved into hybrid forms, and it has found new ways to hush up misconduct and general facts. We might not see the weapons or the soldiers, but every aspect of our lives is affected by the work these people do. Every time you travel, or buy imported food; actually, every time you identify yourself as having a nationality, it’s because of them. Military defense institutions are the reason why States exist, why borders matter, why we speak a certain language, and why you can’t simply put up a tent at the beach. Still, military presence can become even more prominent in daily life, and during supposedly peaceful times.

The chance of a military regime in Brazil has been floating around in conversation since before Bolsonaro’s election. He has notoriously defended the military dictatorship of the 60’s, and the man who was responsible for the torture of Dilma, Brazil’s first female president, during this period. He was a military officer during the dictatorship, and he said he wouldn’t accept the outcome of the Presidential election if he didn’t win.

Here are the numbers:

In his 27 years in congress, Rio de Janeiro was a target of 36 Armed Forces operations, the first one in 92 was also the first in the country. The cases when the AF are used to control the Brazilian population are called GLO’s, ‘Guarantee of Law and Order’. Of the total directed at urban violence, 43% happened in Rio. While most other states had 0, 7 states had 1, and 3 had 2- Rio had 10 (Not counting 1 operation that had 15 phases). Now that he is president, the hyper militarization of Rio is expected to spread throughout Brazil.

There are some expected implications to military presence in terms of public safety, and “law and order”. The military will be used as cops, the public perception of crime will drastically change, and the privatization of prisons will make it all highly profitable. But what I’m interested in exploring with this article is how the Armed Forces (AF) affect women in particular (inside and out of the institution), and the socio-political implications of the historic male dominance of the field.

MISOGYNY

Women have been introduced into the AF only recently. There was particular pressure for this to happen during Dilma’s presidency, as there were no high-ranking women yet. As a side note, I’d like to remind the reader that Dilma was impeached in 2016, and the wife of the man who took her place was praised for being “beautiful, modest, and of the home.” These are passive aggressive methods to keep women “in the home” (and in this case out of the absolute highest office in the country), but there are aggressive methods as well, visible in the alarming figures of hate crimes against women and LGBTQ people.

Introducing women into the AF might not be the solution to sexism, but after starting this research, I realized that it could bring quick and significant changes to the lives of marginalized women, to whom interaction with the AF is inevitable. A long-term solution could be the de-militarization of humanitarian aid and health resources. The first is only quicker because it has already been discussed for a few decades, and the change has happened slowly, while the latter hasn’t even entered the realm of consideration.

In 2011, a study was published on the insertion of women into the Navy. This is the opinion of an officer about how this change has been:

“Sometimes we see that, because of the co-existence of men and women in the Navy, there are involvements between female officials and soldiers, and officials and female soldiers. […] I’m referring to intimate extramarital relations, that the man should be looking for out there, and ends up looking for inside the Navy. [… T]he women [also] introduced another language. There are words that are in the Naval tradition, and a lot of things changed […].”

-Story on page 90 of a 2011 paper called “Public Policy of Gender: Inserting women in the Brazilian Navy as soldiers.”

Let’s unpack this slowly. Firstly, I must say it was difficult to pick one quote to analyse; this paper is filled with uncomfortable sexist remarks veiled as “not-sexist” because they are delivered as compliments or as straight-forward facts. For instance, “it’s great to have women in the Navy because the work environment is much tidier and cleaner” (page 91), as if one great thing women have to offer is their inclination toward domestic work. This attitude completely ignores the oppressive socio-political conjuncture that has caused women to perceive domestic duties as their (unpaid) responsibility, while the man goes out to do the real (paid) work. The environment is also much “gentler”, “studious”, there is less cursing, and they need to watch their “vulgar language”. Aside from the fact that they find the presence of women in bathing suits “embarrassing” during physical training.

Note that female officials and female soldiers are specified as female, while the male ones are omitted and implied. This represents inequality in term choice, a language which later he describes as traditional. He specifies maleness only when describing sex as what men look for. This is feminism 101: treating sex as something men do to women is symbolic of the concept of rape culture. “Extramarital” and “out there” are alarming terms that calls for urgent and thorough research on how these men treat local women in the regions they settle in for work. If rape culture emanates from a language that is considered traditional, we cannot ignore how this language reveals an attitude that might be acted upon at any moment.

Unfortunately, there are no figures or data regarding sexual misconduct by soldiers and officials, only endless stories of men cheating on their wives.

LACK OF DATA

There is lack of data regarding sexual assault, harassment, and other gender based moral attacks perpetrated by members of the Brazilian AF. In a report from a meeting of the Gender Commission of the Ministry of Defense (GCMD) in April of 2015, a representative of the Secretariat of Personnel and Education states that there is no formal registry of assault cases because the ““system” tends to hush up facts that occurred”. Soon after, a male representative of the Institutional Organization Secretariat says that it’s important to establish the purpose of this sort of research, and to manage expectation of results. He claims to have done the research, finding insignificant numbers of cases, some of which include men as the actual victims. Therefore, he expressed concern for the tendency towards hollow “denunciationism”, simply ignoring more than one person’s affirmation that there are no figures on the topic (and no other clear explanation for why that is). This year, a female Naval lawyer explained to me that these figures don’t exist because they are considered personal information processed by the courts; inside the AF, only Intelligence personnel has these reports. In other words, reports and figures exist, but in secrecy.

The dialogue in this context screams of masquerade, especially when it ends admitting that these meetings are a response to the pressure posed by International Relations to meet standards of gender equality. A Minister’s closing statement described Sweden denying diplomatic agreements with Saudi Arabia over the issue of Women’s Rights.

The same meeting fostered a debate over the use of the word “equity”, since some worried that it might be taken too literally; as in the expectation of 50/50 participation of men and women in the AF. Would that be so bad? To them yes, because that would mean replacing meritocracy with some type of affirmative action- as if women have had the choice of entering the AF, and when so, have had the psychological will to be moulded into a violently masculine environment where not even the facilities are designed to accommodate them.

The GCMD still assures that female spaces are only granted within a system of meritocracy (2017). What this means is not so much that women can enter when they are qualified and valuable, but instead when they have effectively lived up to the existing (male) standards that were established by Military institutions 200 years ago.

Meritocracy is nothing more than an excuse to marginalize.

Their meeting records from 2014 already reveal subtle clashes between the ‘talking about’ women’s issues versus actual female participation in these talks. A coronel announced a workshop on The Protection of Women in UN Peace Operations and Maintenance, which was about how to protect a local female population during “peace” missions. However, there were no more spots available for members of the GCMD, which lead a female Tenant, member of the Superior School of War, to immediately lay out the embarrassingly low percentage of women in the educational institution (18%). Usually these low percentages are blamed on the fact that women only sign up for the Army voluntarily, while for Brazilian men it’s compulsory. All long-term Army carriers are voluntary; men are under no obligation to serve more than a year, and the fact that these 9-12 months are compulsory for men only ensures the masculine predominance in the field.

COLONIALISM

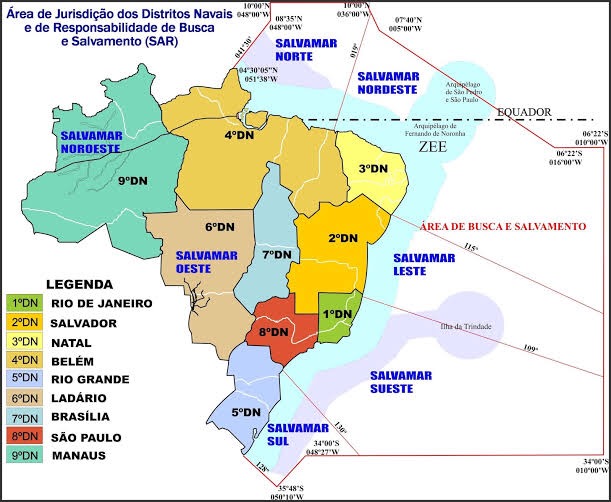

A line officer from the Navy described to me the advice given to newcomers of the 9th, 6th and 4th Naval districts of Brazil:

“Ribeirinha women are easy, but opportunistic, and go after child’s pension. So, make sure not to impregnate them. Don’t even leave the condom laying around- flush it down.”

This advice is about hushing up evidence of sexual misconduct while off duty. The line officer also told me that he’s seen co-workers spend over 20 thousand reais on a weekend “partying” with local women. Some live extravagant lives in impoverished areas and enjoy being sought after for their wealth. These districts include the most vulnerable population of the country, and also the highest number of indigenous peoples; it includes the Amazonian state, and where the Amazon river meets the ocean. River-side populations, called Ribeirinhos, are considered Indigenous or Quilombola.

Here is a culture within a colonial institution that, to this day, endorses taking advantage, sexually, of women of color (Indigenous and of the African diaspora). Even if sexual assault happened and got reported, neither the perpetrator nor the authorities hearing the case would come close to interpreting it from a perspective any other than one plagued by toxic masculinity and colonialism. Is it not likely that an environment that has been exclusively male for a couple hundred years cultivates a culture that demeans and objectifies women? And are there not clear traces of colonialism on these men’s description of sexual encounters as being a ‘privilege’ to the women?

“It’s an advice that shows the normalization of sexual abuse often in power over the most vulnerable. The dehumanisation of these women in describing them as opportunistic disregards how their life-conditions have been deeply shaped by ongoing exploitation.”

-Jördis Spengler, sociologist, author of “On Silence – restricted narratives of gendered sexualized violence”

The “Protection of Women in UN Peace Operations” workshop from 2014 seems to not have been fruitful up to now. Could it be because it was predominantly lead by, and attended by, men? Have these meetings, groups, or sub-institutional acronyms made significant advances in Women’s welfare in this century, or do they exist as no more than an international relations facade displayed for the West?

PREPOTENCY

The Maria da Penha Primer, an informative 40 page introduction to a ground breaking law dedicated to combatting domestic violence in Brazil, describes one relevant aspect of the perpetrator as ‘prepotency’ (‘prepotência’).

Members of the AF tend to be attracted to the role exactly for the power and influence it offers, not only in terms of access to heavy artillery, but also in the sense of reputation, money, control, and entry into highly exclusive physical spaces.

In Brazil, the AF don’t only ensure the sovereignty of the State, they are used to control civilians. A significant part of the police force is already militarised, but we also count on the actual Military for back up in those special occasions, the so-called GLO’s. In many cases, these operations are about land and resources, and are used against the population in the favelas, indigenous communities, quilombos, and protests.

The sovereignty of the favela and its population;

Indigenous and Quilombist peoples’ access to forests, mangroves, rivers, and other sources of spiritual, cultural, and practical sustenance;

Anyone voicing their opinions and frustrations through protests in cities;

These are all considered threats to the State, and warrants waging war on civilians.

Article 331 of the penal code ensures the right for these armed authorities to criminalize contempt. Since contempt is an abstract concept, it’s easy for cops and soldiers to simply arrest you for antagonising them in any way. Not obeying their orders will mean an assault against ‘State function’, resulting in up to 2 years detention. That is if you didn’t do it for political reasons, in which case it could be categorised as terrorism, resulting in a new sentence.

This is them having greater power and influence- the definition of prepotency. While that isn’t evidence of any crime in itself, it shows the urgent need of gender education for members of defense institutions. It represents a culture inside the AF, and how changing this culture is an arduous job within such rigidity.

The Center for Strategic Studies of Defense (CEED), a multi national and somewhat independent initiative, began conducting research on women in the Latin American defense sector around 2015. Today, it’s still unclear what the result was, and Brazil’s defense ministry’s willingness to participate.

Perhaps the research questions already begged for considerable action. Section 5 of the form, dedicated to Work Environment, asks about the existence of an office dedicated to women’s welfare, domestic violence support, registry of harassment cases, and sexual education programs. Of the officers I’ve met, none are aware of the existence of these programs, of the existence of this research, or have been exposed to any exchange of the sort.

CONCLUSION

We can’t wait until there is unanimous agreement over the fact that the Patriarchy and the State are problems before we can begin implementing solutions. We need to make demands now. There has been and will continue to be tremendous resistance against change. Undermining hegemonic structures feels terrifying to those who can’t imagine their lives or the world without them. It comes down to an utter lack of creativity, and just enough privilege, for an array of excuses to keep us on a fatal course.

Losing faith in meritocracy can go a long way to stir things in a direction where the word “marginalized” won’t have a negative connotation. Men losing the right to spout hateful language can go a long way toward empowering women to take up space. And perhaps this will translate into a significant changes in Military attitude toward women in vulnerable regions.

As an anarchist, I did not expect to conclude anything other than an even firmer opposition to the idea of anyone joining the Armed Forces. However, do women really need more people telling them what they should and should not do? Perhaps this is one of those situations like gay marriage; first we need to make it legal for gay people before we can start undermining the institution altogether.

So, here is a shout out to women:

Be a proud vibe-killer!

Their right to be offensive and ‘traditionally masculine’ isn’t more important than your right to not be dependent, to not be harassed, to not be demeaned, to not be killed, to not be raped, to not be bought, to not be catcalled, to not be anything you don’t wanna be.

Then, you can start being everything you wanna be.

______

Text by Mirna-Wabi-Sabi